Dir. Julian Schnabel, biography, drama, UK, France, USA, 110 min., 2018.

A film about the last two years of Vincent Van Gogh’s life. The director omitted 35 years of the protagonist’s life and began from the moment when he matured as an artist and stood “at eternity’s gate”. The film begins with the events of 1888, when Van Gogh moved to the south of France — to Arles. He fled from an alien trading environment and a public that did not accept him. With the support of his brother Theo, Vincent intended to create the “Workshop of the South” — a union of like-minded artists.

Biographers write about Van Gogh’s isolation. He hardly got along with people. All his attempts to create a personal life have failed. Throughout his life, the artist was friends only with his brother Theo. And when Van Gogh found a common language with Paul Gauguin, the value of such friendship for Vincent was unusually great. Paul Gauguin also arrived in Arles, where he spent a lot of time with Van Gogh — on the plain air and on walks, which were accompanied by frank creative conversations. When Gauguin announced his departure, Van Gogh took the news as a personal tragedy. The intolerable emptiness from the loss of a friend and like-minded person turned into an attack. The artist cut off his earlobe — this moment, captured in the picture by Van Gogh himself, gave the director his own reading. Some researchers believe that this was not an attack of despair, but insanity. The artist quite often took absinthe, which could also affect his psyche. However, the next day Vincent was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where the attack was repeated with renewed vigor. Which may indicate that most likely the reason that prompted Van Gogh to go to self-harm was still despair and the subtlety of his nervous organization.

Some doctors actually believed that Van Gogh suffered from a variety of mental disorders. Some of the artist’s contemporaries expressed the opinion that the psychiatrists who treated Van Gogh were more likely to harm him than help. Schnabel also adheres to this point of view, contrasting in the film the open and naive, like a child, artist to tough, icy people in white coats. Just as cold and heartless the priest appears before the viewer whilst talking with Van Gogh. This is a reference to Pontius Pilate — to the Roman prefect, who sent Christ to execution at the behest of the crowd. It seems that the director refutes the thesis about Van Gogh’s madness, and, rather, sees a visionary in the artist. It was the innovative pictorial language, Vincent’s ability to look into the future that became the reason for the misunderstanding and contempt of society.

The residents of Arles demanded that Vincent be placed in a hospital. Where he settled on the condition that he would have the opportunity to paint. It seems that he did not particularly care about where to live — the main thing was to be able to paint pictures. In the hospital Saint-Paul, not far from Arles, the artist was tormented by the “fire of the soul”, prompting him to work constantly — about which Van Gogh wrote in his diaries. He paints pictures tirelessly.

During the year — the time spent in the hospital — he created more than one hundred and fifty paintings and about a hundred drawings and watercolors. The speed and stress of work exhausted the artist. Neither his life nor his work endured the atmosphere of the hospital. As a result, he shot himself with a pistol to scare off crows, thereby inflicting a mortal wound on himself. The director shows the circumstances of the artist’s death unclear and vague, since some researchers believe that the shot was made by teenagers.

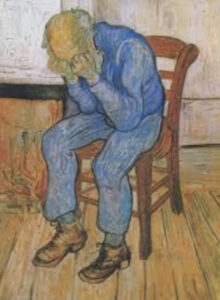

And again returning to the title of the film: “At Eternity’s Gate”. Van Gogh repeated one of his paintings, which he called “At Eternity’s Gate” (1890). This is an image of an old man sitting on a chair. His elbows are on his knees, his head is lowered in grief on his hands. This work was inspired by Thomas Moore’s poem «Oft, in the Stilly Night»:

Oft, in the stilly night,

Ere Slumber’s chain hath bound me,

Fond Memory brings the light

Of other days around me;

The smiles, the tears,

Of boyhood’s years,

The words of love then spoken;

The eyes that shone,

Now dimm’d and gone,

The cheerful hearts now broken!

Thus, in the stilly night,

Ere Slumber’s chain hath bound me,

Sad Memory brings the light

Of other days around me.

When I remember all

The friends, so link’d together,

I’ve seen around me fall

Like leaves in wintry weather;

I feel like one,

Who treads alone

Some banquet-hall deserted,

Whose lights are fled,

Whose garlands dead,

And all but he departed!

Thus, in the stilly night,

Ere Slumber’s chain hath bound me,

Sad Memory brings the light

Of other days around me.

This poem found a response in the soul of the artist. According to his brother Theo, the last thing that Van Gogh said before his death: La tristesse durera toujours (“Sadness will last forever”). The whole film is permeated with sadness and hopelessness. The artist renounces the world in order to become a genius. This is the inevitability of his fate. Despite the non-recognition and ridicule of others, Vincent believes in his predestination. The director conveys fits of insanity, a break in Van Gogh’s consciousness, his gradual renunciation of life.

For this, a camera trick is used, already used by Schnabel in other films, such as a camera shake. As a result, the viewer develops dizziness — a kind of slight clouding of consciousness. The director (and screenwriter rolled into one) abandoned the plot. The film is shot as a cinematic essay through Vincent’s eyes. Large first person shots prevail.

The bright juicy painting of Van Gogh’s paintings convey the breathtaking views of the nature of the south of France, accompanied by the lively sounds of swaying grasses and branches. The artist creates strokes on the canvas in the rhythm of the music of Tatiana Lisovskaya. Meditative shots, enhanced by slow, viscous music, are interspersed with the dialogues of the characters, which are akin to philosophical reflections. In simple words and phrases, deep meaning and acuteness of feelings are expressed.

There are very different opinions about the film, from enthusiastic to strongly negative. But what unites the opinions of all viewers and critics is the impeccable selection of the actor for the main character. Willem Dafoe is not only similar, he is like a revived self-portrait of Van Gogh.

Schnabel took on an unusually difficult job of conveying the inner world of a genius and, in the opinion of most, a sick person. Of course, the director let everything through himself. He showed not only Van Gogh, he showed himself through Van Gogh. It happened once that I was painting a copy of Van Gogh’s sunflowers on the white wall of a house. Despite the rather simple drawing, execution proved to be a very difficult task. Moreover, difficult not technically, but emotionally. A gloomy mood came over me, I woke up at night and really wanted to finish my work soon, which turned into a real torture. It seems that the rebellious spirit of Van Gogh, to some extent, was transmitted to me.

You can imagine what kind of emotional tests the director went through, creating this film, forced to immerse himself not in one picture, as happened to me, but in many. And if we add Vincent’s diaries and contradictory information from biographers to the pictures… Perhaps this film is for the prepared viewer, who is familiar with biography, diaries, and paintings by Van Gogh; matured to come closer to understanding Vincent van Gogh “At Eternity’s Gate”.